Walter Davis understood from a young age that he was a bit different from other children.

“My parents instilled in me that while I was different from other kids, I was still very capable. And that is how I lived my life. I could still do things, I just did them in my own way,” he said.

The difference came in the form of a blood disease called sickle cell — a disease that Walter was born with and first diagnosed at the age of three.

Sickle cell disease is the most common inherited blood disease in the world. The disease affects blood cells in which normally round blood cells take on a crescent or “sickle” shape. Due to their unique shape, sickle cells have a difficult time traveling through small blood vessels. By blocking blood flow, the sickle cells prevent oxygen and nutrients from reaching organs and tissues. This can cause what is known as a sickle cell crisis. During a sickle cell crisis, patients can suffer from severe pain, tissue damage, strokes, organ failure and other serious health complications.

Walter experienced his first sickle cell crisis at the age of three.

“I was so young at that time but I remember being in and out of the hospital and I remember the pain,” Walter said. “The pain is something that was a constant for me. I don’t remember a time in my life that I was not in pain.”

Pain is one of the most common complications for patients who battle sickle cell disease, explains Wally Smith, M.D., Florence Neal Cooper Smith Professor of Sickle Cell Disease at Virginia Commonwealth University and medical director of the adult sickle cell program at VCU Health. Health care options to treat this disease have historically suffered from underinvestment.

“Until recently, patients who were born with sickle cell disease were told two things. First, that they would not live to see adulthood. Second, that they were going to live a life filled with pain – the worst kind of pain that you can imagine,” Smith said.

Walter describes the pain he has experienced as beating, stabbing and aching sensations that made it nearly impossible for him to function on a daily basis.

“Imagine playing baseball and getting hit with a metal bat in the shin. But times that by a hundred and then repeat it over and over and over again. It doesn't take a day off,” Walter said. “On a bad day, I couldn’t get out of bed. It was so debilitating.”

“Imagine playing baseball and getting hit with a metal bat in the shin. But times that by a hundred and then repeat it over and over and over again. It doesn't take a day off,” Walter said. “On a bad day, I couldn’t get out of bed. It was so debilitating.”

But Walter refused to let the disease and pain define him.

As he grew from childhood into adulthood, he found various activities and outlets that allowed him to push his own limits and redefine what was possible, such as football and boxing.

Walter’s unbreakable resolve to continue pursuing his passions is mirrored by the determination of sickle cell disease experts at CHoR and VCU Health to find a cure for this debilitating disease. Through the pediatric and adult sickle cell programs’ team approach, providers have made historic strides to improve the quality of treatment for patients under their care.

Football is a grueling sport for the healthiest of athletes, so it was almost unheard of for a player to be battling sickle cell disease. Walter was determined to prove everyone wrong.

“Everyone told me I could not play football. They thought I was crazy,” Walter said smiling. “But I knew I could. For me it was an outlet. It was the opportunity to inflict a tiny bit of the pain that I was feeling onto someone else, an opportunity to channel some of the frustration that I was feeling.”

“I met Walter when he was 15 years old,” Smith recalled. “He was the big man on campus playing football at his high school, the darling of all the cheerleaders. He was doing really well during that period.”

Walter wanted to play professional football, so the team at VCU Health introduced him to Ryan Clark, a former professional football player and sickle cell disease advocate. Clark had also been impacted by sickle cell disease, as a carrier of the sickle cell trait.

In Walter’s mind, he was going to be just like Clark, overcoming the odds to play professional football; to reimagine what was possible while living with sickle cell disease.

But then the disease grabbed hold of him and would not let him go.

After high school, Walter’s physical function began to decline. He lost the ability to run wind sprints and lift weights. His pain level continued to increase. He became depressed and suicidal.

“It was a very dark period for me,” Walter said. “If I’m being very honest, my last suicide attempt really woke me up and I knew that I needed to make some changes. I knew that I was meant to be here for a purpose, I just wasn’t sure what that purpose was.”

During this period of darkness for Walter, strides were being made in the field of sickle cell treatment.

Sickle cell experts at CHoR and VCU Health, where Walter was being treated, were about to embark upon a clinical trial for treatment that, if proven successful, could revolutionize how sickle cell patients were cared for.

The new treatment was gene therapy. Gene therapy works by giving red blood cells new instructions for producing hemoglobin that will prevent red blood cells from sickling. It requires the collection of a patient's stem cells from their bone marrow. After the stem cells are collected, they're sent off to the lab and they're processed in one of two different ways: They either add a new hemoglobin gene or induce the production of fetal hemoglobin that does not sickle.

Those new cells are then sent back and infused into the patient. Once infused, the patient now produces lower levels of sickling hemoglobin.

VCU Health, a clinical care leader for sickle cell for decades, was selected as one of the locations for the clinical trial.

“VCU Health has been at the forefront of developing new treatments for sickle cell disease, drugs and other treatments, but also at the forefront of bone marrow transplantation to cure sickle cell disease,” Smith said. “With the depth of expertise and our facilities here, we were a natural place to set up to test this gene therapy.”

With the clinical trial location secured, the team now needed to identify a perfect candidate for the trial. And it was Walter who became a key player, stepping into the ring once again.

Led by a comprehensive team of doctors at CHoR and VCU Health, Walter was enrolled in the first cohort of the clinical trials for one of the new gene therapy treatments.

Led by a comprehensive team of doctors at CHoR and VCU Health, Walter was enrolled in the first cohort of the clinical trials for one of the new gene therapy treatments.

The treatment is a multi-step process that involves significant planning and preparation, involving a team of dedicated experts.

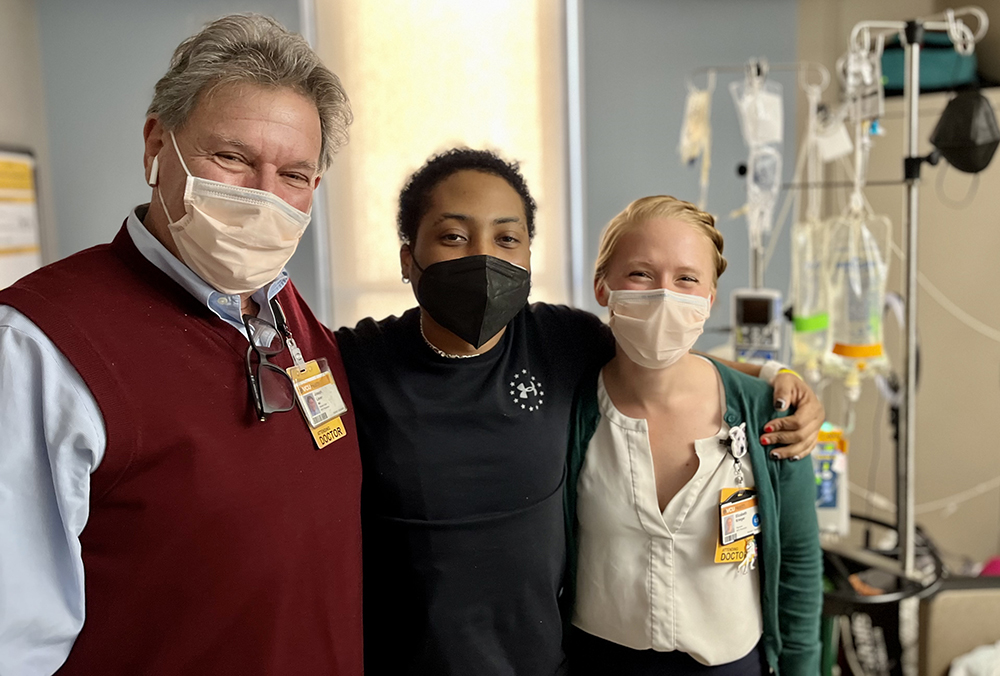

Beth Krieger, M.D, a pediatric hematology and oncology specialist at CHoR, led the gene therapy treatment. She collaborated closely with Mica Ferlis, ACNP, and India Sisler, M.D., who has been caring for Walter since he was young, more recently helping him make the transition from pediatric care at CHoR to adult sickle cell experts at VCU Health.

Oftentimes in medicine, new and exciting medical breakthroughs are first established in the adult population before trickling to pediatrics. Pediatric bone marrow transplanters, like Krieger, have long been the pioneers in seeking a cure for sickle cell disease. In this case, the pediatric providers are the true experts in gene therapy. They are not only treating pediatric patients, but young adults, like Walter, as well.

Krieger and Sisler worked closely with the adult sickle cell team, including Smith and Thokozeni Lipato, M.D., to ensure Walter received the best pain management and coordination of services throughout the entire process. Walter was also supported by a team of nurses, patient navigators and technicians who were there each step of the way.

“It truly is a team effort,” Krieger said. “This process takes about a year. A major part of preparing for the journey is done while we're doing those exchange transfusions beforehand. We have to remove medications that the patient can't be on while they're having the therapy. And we're getting them mentally and physically prepared for the gene therapy itself.”

This team approach is part of what sets VCU Health apart and part of what made it an ideal location to be a leader in the clinical trial.

“In order to become a site for the trial, we had to show that we had the infrastructure to support it. We had to show that we had the team, the resources and the research foundation,” Krieger said. “So much goes into this process that many people don’t see.”

For Walter, the process wasn’t easy. But he trusted his care team – the same team that had seen him during his highest moments as a football player at Colonial Heights High School to his lowest moments as he struggled as a young adult.

For Walter, the process wasn’t easy. But he trusted his care team – the same team that had seen him during his highest moments as a football player at Colonial Heights High School to his lowest moments as he struggled as a young adult.

“It was a long, long, arduous process,” Walter said. “But I’m so thankful for the team. They said, ‘trust them’ and they would deliver. They delivered and so much more.”

Now, two years after the start of his gene therapy treatment, Walter’s care team will monitor his progress for the next 15 years to see how the treatment plays out. In the meantime, Walter and his care team describe him as a ‘transformed’ man.

“We don’t use the word ‘cured’ yet,” Smith said. “I say ‘transformed’ because we are still in the monitoring phase. Walter will continue to be monitored for at least the next 15 years. But the transformation that I’ve seen has been simply remarkable. Walter is a new man, with a new lease on life.”

The pain that wrecked Walter’s body so often has been greatly reduced, giving him his life back.

“I feel amazing. I never thought I would feel this good ever again,” Walter said. “I get teary-eyed when I sit and think about it because people tried to convince me that I wasn't feeling the pain I was feeling. They tried to tell me that I wasn’t in that much pain and that I didn’t need the pain medication that I was on. To look back and see the place that I’m in now… It’s truly amazing.”

With this new lease on life, this 30-year-old is now rediscovering himself. While he no longer plays football, he has found other outlets to express himself; including boxing and painting. And, perhaps his most important accomplishment to date, being a voice for others who have suffered silently through sickle cell.

Looking back, he reflects that part of his newfound sense of purpose is to share his journey with others.

“We all have a part to play,” Walter said. “I know now that my part was to be a pioneer in this clinical trial and to be able to share my story with other people who are going through something similar.”

So what’s the next chapter for Walter?

“It’s still being written,” Walter said with a smile. “And I’m the one that’s writing it and that’s the most important thing.”

While Walter was the first patient to participate in gene therapy at VCU Health, he will not be the last.

While Walter was the first patient to participate in gene therapy at VCU Health, he will not be the last.

On December 8, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two gene therapies to treat sickle cell disease in people ages 12 and older, revolutionizing the way that sickle cell disease is now treated.

VCU Health is currently the only health system in Virginia offering the new treatment.

“It has been energizing and completely exhilarating to be a part of the development of the cure for sickle cell at VCU Health,” Krieger reflected. “I'm so excited about what the future of sickle cell care holds and I'm just thrilled to be able to bring this to more patients.”

By Danielle Pierce

Boxing photos by Allen Jones, VCU Enterprise Marketing and Communications

This story originally ran on VCU Health News.